Extrapulmonary tuberculosis (TB) – i.e. when the disease presents outside of the lungs – has existed since antiquity, as evidenced by studies in paleopathology.1 The skeleton is a common site for extrapulmonary TB, but isolated rib TB is rare.2 One in 50 patients with musculoskeletal TB will have rib involvement.2–4

Extrapulmonary TB is more common in areas of lower socioeconomic status in Asia and Africa and in immigrants from these areas to the developed world.5 Rib TB can involve single or multiple ribs. However, it is rare, especially in its isolated form, and less than half of patients with rib TB have concomitant pulmonary involvement.4 It is now clear that rib TB can affect patients with both intact and compromised immunity. Rib TB can elude diagnosis, especially in its early stages when complications can be prevented, so a high index of suspicion is needed to make an early diagnosis. Appropriate imaging and other studies help to differentiate it from other conditions.

This case report describes a patient with isolated rib TB and discusses the problems in managing such patients in a low-income setting, where the disease is most prevalent. Advances in the pathophysiology, investigation and treatment that may help manage this condition more effectively in the future are discussed.

Case report

A 41-year-old male from a lower socioeconomic status background in rural South India presented with a 6-week history of low-grade fever, left-sided chest pain, unintentional weight loss and fatigue. He was treated unsuccessfully by three physicians prior to the presentation. The fever occurred daily without any pattern and without chills or rigour. The chest pain was localized to two points on the left-sided chest wall, over the fifth rib laterally and the seventh rib posteriorly, near the costovertebral junction. The pain was aggravated by deep inspiration and voluntary coughing. The patient reported unusual fatigue and could not attend work. There were no significant symptoms relating to the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal or neural systems. Specifically, he denied pain in the joints or spine.

His past medical history was unremarkable. He had experienced no trauma to the chest or previous hospitalizations or surgeries. He did not smoke, drink alcohol or use recreational drugs, and was in a monogamous relationship. He had no pets, had not travelled recently and had no exposure to occupational diseases. His mother had pulmonary TB 30 years ago and was treated successfully.

Physical examination was notable for his 10% weight loss and pallor, but no icterus or lymphadenopathy was seen. The respiratory, cardiovascular, abdominal and neurological examinations were unremarkable. Examinations of the joints and spine were normal; however, there was exquisite tenderness over the fifth and seventh ribs on the left-sided chest wall, as the patient reported in his history. Additionally, a hemispherical swelling was seen, which had recently developed over the left-sided posterolateral chest wall: this swelling measured 12 cm x 5 cm, was soft, non-compressible, without erythema or tenderness and did not trigger a cough impulse.

Initial laboratory evaluation

The patient’s haemoglobin levels were 11.7 g/dL (14–18), his platelet count was 188,000 cells/mm3 and his white blood cell count was 11,500 cells/mm3, which comprised 49% neutrophils, 43% lymphocytes and 8% monocytes. His erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 100 mm/hr and his blood glucose was 98 mg/dL. Liver and renal functions were normal, and the tests for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) types 1 and 2 antibodies and p24 antigen were negative. The Mantoux tuberculin skin test was positive at 16 mm induration. Chest X-rays taken by previous providers showed no abnormalities of the heart, lungs or thoracic cage.

Further tests

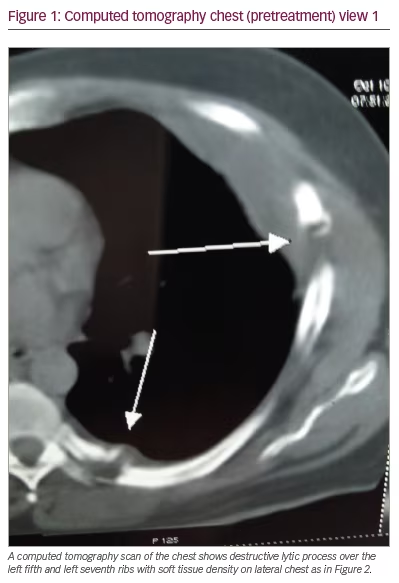

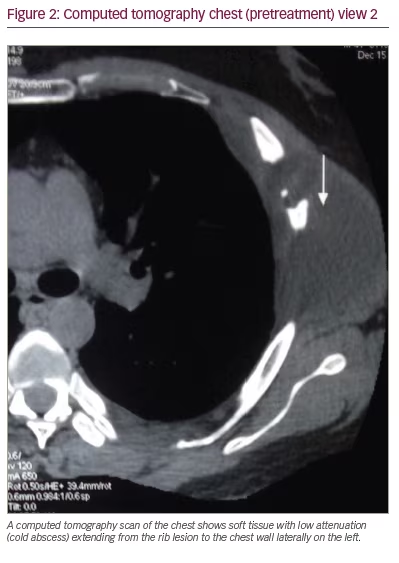

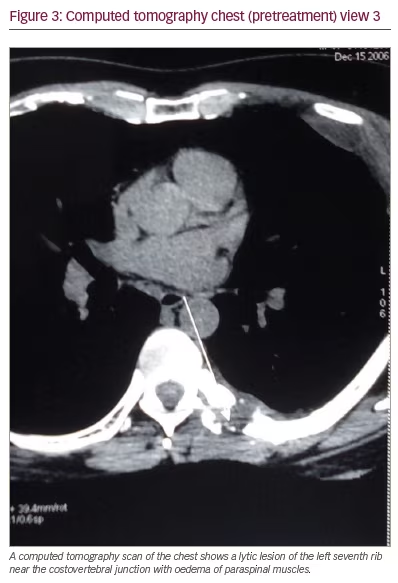

Because of the pain and point tenderness over the left-sided chest wall, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered. The scan revealed a lytic lesion of the left fifth rib laterally, a soft tissue mass extending from the left fifth rib outward to the chest wall and a lytic lesion of the left seventh rib near the costovertebral junction with reactive inflammation in the nearby paraspinal muscles (Figures 1, 2, and 3). The spine, pleura, and lung fields were normal, and no enlarged intrathoracic lymph nodes were seen.

Subsequently, the patient denied consent for a biopsy of the rib lesions, so the left chest wall swelling was aspirated instead. Sixty millilitres of straw-coloured fluid were obtained. The spun sediment was examined, revealing a mixture of lymphocytes, polymorphs, epithelioid cells and karyorrhectic debris. Smears and cultures were negative for bacteria (including acid-fast bacilli) and fungi. The MycoReal real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test uses sensitive probes that reliably distinguish Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) from other mycobacterial species.6 This test has been validated for both pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB and compares well with other similar tests in use. MycoReal real-time PCR of the spun sediment from the aspirate in our patient was positive for M. tuberculosis, showing a positive specific amplification for this species but not for other mycobacteria. PCR sensitivity testing for anti-tuberculous drugs was not done as it was unavailable.

Pulmonary TB was deemed unlikely because of the absence of cough or sputum, the negative chest X-rays and the chest CT scan that revealed no infiltrates suggestive of pulmonary TB. Additionally, the CT scan revealed no pleural or mediastinal lymph node disease. Since the patient’s pain was aggravated by voluntary coughing, sputum induction procedures were not done for fear of worsening the pain in the affected ribs, possibly causing fracture or other complications.

A diagnosis of isolated TB of the ribs was made, and the patient began directly observed anti-tuberculous therapy according to weight-based guidelines.7 The patient received rifampicin 600 mg daily (10 mg/kg), isoniazid 300 mg daily, ethambutol 1,200 mg daily (15 to 25 mg/kg) and pyrazinamide 1.5 g daily (15 to 30 mg/kg) for 2 months then continued rifampicin and isoniazid for a further 7 months. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) 40 mg was given daily for the entire 9 months. The patient was counselled that if his condition did not improve in the first few weeks, surgical management of the lesions might be necessary.

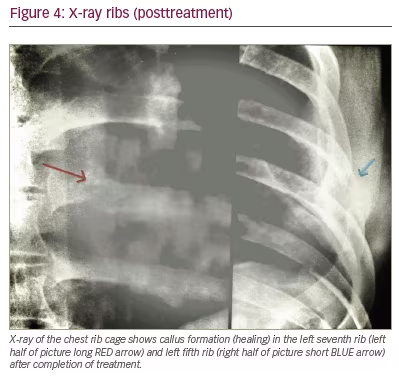

The patient improved with the medical treatment. His fever subsided after 2 weeks, his appetite improved, he regained weight and the fatigue gradually abated. The pain over the affected ribs vanished, and the cold abscess diminished in size progressively and disappeared within 4 months without sinuses, scars or the need for surgery. X-rays of the ribs taken a year later (Figure 4) showed healing with callus formation.

The patient has been followed up regularly and has been disease- and symptom-free for the last 16 years, suggesting the initial diagnosis correct.

Discussion

Most cases of rib TB result from haematogenous spread from a site of reactivation of primary TB. In a minority of cases, rib TB is due to contiguous spread from neighbouring pleuro-pulmonary disease.2 In our patient, a contiguous source was absent, and clinical evaluation revealed no source of reactivation from which the disease could have spread to the ribs. As in our patient, rib TB can be present in one or more ribs, and some patients may have concomitant disease at other skeletal sites like the spine, sternum, large joints and the skull. Lynn et al. have described multifocal skeletal TB (including rib lesions) in an immunocompetent patient.8

Co-existent pulmonary disease is invariably absent in patients with rib TB, as it was in our patient.9 Nakiyingi et al. have reported on a young man with rib TB involving two ribs, constitutional symptoms, no lung involvement and excellent response to medical therapy similar to our patient.10

Apart from constitutional symptoms, local clinical clues include pain and tenderness over the affected ribs and cold abscesses (both present in our patient), cough from irritation of the parietal pleura, chest wall sinuses as an advanced complication and bony sequestrum on imaging. In our patient, the point tenderness were early warnings of a rib pathology in the absence of chest wall trauma. Initially, this was wrongly identified as a musculoskeletal complaint in a febrile illness, thus causing a short delay in diagnosis. Despite this, the diagnosis was swift enough to enable timely treatment to prevent the formation of chest wall sinuses and recalcitrant disease needing multiple interventions. This is not always the case; for example, Liang et al. reported an immigrant patient with persistent, non-specific back and rib pain that finally proved to be rib TB.11 Further, in 1999, Chang et al. analysed 12 surgically confirmed cases of rib TB and found that chest pain, chest wall masses and draining sinuses were the main presentations.12 The diagnosis was often delayed due to confusion with other conditions and poor choice of diagnostic tests. Based on this analysis, the authors made recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of rib TB: they recommend taking a thorough history, detailed physical examination, CT imaging, nuclear bone scan and confirmation by biopsy. They advocate surgery where the diagnosis is still in doubt or when the response to medical therapy is suboptimal.12

Since the guidelines by Chang et al. have been published,12 the M. tuberculosis PCR test has become invaluable in establishing a speedy diagnosis and can provide an alternative tool when a biopsy of the rib lesions is unsuccessful or unavailable.13 Continual refinements in this technique are further improving its accuracy and turnaround time.

When lytic lesions are detected in the ribs, many conditions come to mind: the most common is metastatic disease. Our patient did not have a diagnosis of a primary malignancy, nor did he have symptoms to suggest one. Other possible conditions are TB (second most common), primary and secondary bone tumours, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis, eosinophilic granulomas and infections with fungi or amoeba.14–17 In our patient, the contact history, socioeconomic status, constitutional symptoms, lytic rib lesions, presence of cold abscess, a positive tuberculin skin test, very high erythrocyte-sedimentation rate and positive PCR favoured TB.

X-rays are notorious in being normal for the early stages of a disease,18 as in our patient, who had been evaluated earlier by three providers. CT scans are sensitive in defining bone lesions, and they help in planning invasive diagnostic and surgical procedures and in ruling in or out concomitant diseases in the spine, lungs, pleura and lymph nodes. Lee et al. have reviewed CT appearances in biopsy-proven rib TB and have described lesions in various locations, including the rib shaft, costochondral, sternochondral and costovertebral junctions. They found lesions to be osteolytic and expansile with disrupted or irregular cortices. Cold abscesses had low-attenuated centres with a rim-enhancing periphery, and in no cases was an extension into the lung parenchyma noted.19 Our patient had lytic rib lesions, a cold abscess and no pulmonary parenchyma extension. Khalil et al. have discussed the utility of CT in chest wall TB, and they have described a few patients with one or more rib lesions, which is similar to our patient.20

Newer tests for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB that are applicable to rib TB include the T-SPOT™ (Oxford Immunotec, Abingdon, Oxford, UK) TB test, a T cell-based assay, and a quantitative PCR of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded skeletal specimens. Other imaging modalities needing validation for rib TB include single-photon electron/CT fusion imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18 F-FDG-PET) imaging.21–24

Medical versus surgical treatment

Experienced clinicians differ in their treatment recommendations. Even among those who favour medical treatment alone, the recommended duration of therapy is not standard, varying from 6 to 9 months or more.25,26 Those who advocate surgery suggest that it removes the diseased areas, allows medications to better penetrate diseased areas and prevents recurrences.27 Unfortunately, since rib TB cases are so few, randomized studies are impossible, and expert opinion is the only option. One thing is certain: early diagnosis will improve outcomes and prevent complications and recurrences.

Limitations in our patient management and challenges to tuberculosis management in developing countries

It is likely that a more sensitive imaging procedure, such as 18 F-FDG-PET/CT, as studied by Cho et al.,24 may have revealed subclinical foci of reactivated TB in addition to the rib lesions in our patient. Although rib TB biopsies invariably yield no acid-fast bacilli in smears and conventional cultures, the lack of a histological diagnosis of caseating granulomas was a definite limitation in the management of our patient. In the developing world, where TB is most common, affordability and availability of investigations are a challenge. Notwithstanding, most anti-tuberculousis drugs are available at no cost through the National TB Control Program in India. Multidrug-resistant TB is rampant worldwide and is a grave problem in the developing world.28 Our patient responded to first-line therapy, but ideally, anti-tuberculous drug susceptibility testing should be done before starting treatment. This will help choose the appropriate drugs, prevent delays in therapy and reduce morbidity. The unavailability of this test using PCR at that time (2006) in the patient’s geographic area was another management limitation for us.

Recent basic and clinical research in patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis

The HIV epidemic of the 1980s witnessed an explosion of new cases of TB, with its share of extrapulmonary TB, and it was widely accepted that immunosuppression increases extrapulmonary TB.29 This concept has been recently challenged by Shivakoti et al., who systematically reviewed studies spanning 30 years on extrapulmonary TB in HIV.30 They found heterogeneity and bias all the studies that prevent us from drawing firm conclusions of increased extrapulmonary TB in HIV. Furthermore, Leibert et al. have shown that TB of the spine had similar clinical presentation and outcomes in people living with HIV and in those without HIV in contrast to other forms of extrapulmonary TB.31

Antas et al. have demonstrated a decrease in CD4+ lymphocyte numbers and innate immunity in patients with past extrapulmonary TB.32 In a pilot study, Motsinger-Reif et al. showed that polymorphisms in several receptors – including interleukin (IL)-1β, toll-like receptors and vitamin D receptor (VDR) Fok1 from Flavobacterium okeanokoites – are associated with extrapulmonary TB.33 Fiske et al. showed in an in vitro model of macrophages that persons infected with previous extrapulmonary TB had defective production of IL-6, IL-10, tumour necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ, which facilitated not only M. tuberculosis infection but also disease dissemination.34 As part of another research group, Fiske also showed increased VDR expression in macrophages from patients with previous extrapulmonary TB, even though their vitamin D levels were comparable with uninfected individuals.35 Wilkinson et al. showed diminished vitamin D levels and polymorphisms in the VDR that increased the susceptibility to M. tuberculosis infection in Asian immigrants to the United Kingdom.36 Our patient, who lived mostly indoors and consumed a diet not fortified with vitamin D, may have had low vitamin D, which increased susceptibility to extrapulmonary TB. However, we did not measure his vitamin D levels when he presented to us. More large-scale studies to replicate these findings are needed and, if confirmed, will revolutionise the prevention and treatment of extrapulmonary and rib TB.